Another donation came this week; thank you, Justin.

In previous posts we have looked at the construction methods of some of the best-known makers on Savile Row and elsewhere, this time we look at one of the less well-known though no less highly-respected SR houses, Welsh and Jefferies. I, myself, know little of them other than the fact that they have been in business a little over 100 years, and recently acquired the firm Lesley & Roberts. They have the beginnings of a very attractive website, one which has inspired me to try to make this blog more interesting to look at. I also know that their cutter, Malcolm Plews, is one of the most highly regarded members of the trade and is considered one of the best working cutters by his customers and by his colleagues. We can learn little about Mr. Plews by examining a garment without its owner inside it but we can learn a bit about the firm, and perhaps learn something new about garment construction in general.

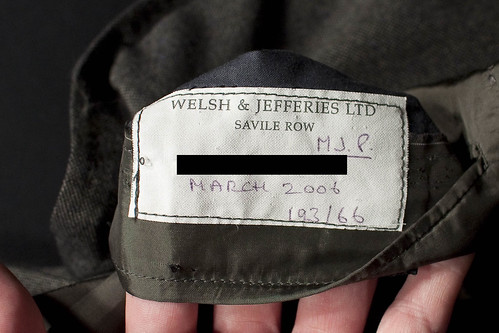

The label inside the pocket indicates that the coat was cut in 2006 and bears Mr. Plews' initials; I have obscured the name of the owner.

It was cut in a proper 3 button style, with three working buttonholes on each sleeve; as I unfasten them I notice the same gummy substance as was used on Steed's buttonholes so it is clearly more widespread a technique than I thought. I'm still a little ambivalent about it, though, as it was a little messy-looking on the dinner suit; here you see it as I try to open the lapel buttonhole.

The shoulder has a good, strong rope to it, as one might expect from military tailors. Not to everyone's tastes, but certainly to mine.

There is a dart under the lapel, which we will pause to discuss for a moment.

Without getting into too much detail about the position of the shoulder point, one of the most hotly debated subjects among cutters, a shoulder can be said to be cut "straight" or "crooked", which have nothing to do with the shape of the shoulder but the position of the shoulder point. A shoulder which is cut crooked has a shoulder point which is further away from the center front than a straight shoulder, the crooked shoulder giving a cleaner, leaner chest than a straight one. It also causes the bridle to lengthen, which can sometimes cause gapping along the roll line or for the coat to swing away at the hem. There are two principal methods of dealing with this extra length- a chest dart which crosses the roll line, as is seen here, or a bridle tape which is drawn tight in order to shrink the excess length onto it. Both methods will help the roll line to conform snugly to the chest without "popping"- most (perhaps all) RTW makers draw the bridle tape, but in MTM orders where the customer has a prominent chest and the lapel still gapes, we will then apply a "full chest" alteration which includes the chest dart so he gets a double-dose of the shortening effects.

In the case of this garment, there is a chest dart so we don't necessarily expect to see a bridle tape inside.

Some garments come right apart in my hands; this one was quite a bit more work to get open, which is a good thing- it speaks to how solidly-constructed it was, as might be expected from a military tailor, and is a good indicator that the coat will last a very long time.

The shoulder wadding is a little unusual in that it extends quite a bit down the back of the scye- not unusual to pad the back of the scye, as the Huntsman example we looked at in a previous post, but just that the pad should be shaped this way. I think this will give a smoother shape and more support and is a good idea for those whose strong blades or poor posture make for a potentially messy back. There are more layers of dense wadding than any other SR garment I have looked at and can be dubbed the strongest shoulder to date.

The canvas has been constructed in the same manner as the Hunstman suit, the dart having been closed by machine onto a silesia tape, closing all layers of canvas, haircloth and felt at once. Notice the very large area covered by the felt- this conceals a large piece of haircloth (the firmest type of canvas available) just slightly smaller than the felt itself, which extends almost all the way down to the waist. This is helped by a generous dose of pad stitching (by hand, of course) and the first of the curiosities- a piece of straight-cut fusible in the armscye are.

A closer look at the fusible, which seems a bit like the Kufner B872 article and was applied after the pad stitching was done

I have no idea what purpose this might serve other than to stabilize the scye, prevent stretching, or perhaps prevent unsightly folds developing (just teasing the drapists). I'll have to sit on this one for a while....

Again, a curiosity. The edge tape is fusible, but has been basted on by hand.

I have seen, from time to time, a piece of silesia inserted underneath the canvas in the lapel, meant to give a bit more bulk and support to the roll, since the more layers worked together, the more stable the shape- I will certainly always put a small piece in the gorge area to stabilize. This is the fist time I have seen the silesia placed on TOP of the canvas before being pad stitched (again, by hand).

The collar has also been padded by hand

A view of the extra pieces of canvas in the shoulder. Where I might use an extra piece or two of haircloth for a very structured shoulder, they have used three pieces of wool canvas. Note, however, that two of the pieces have the hairline running straight up and down, which is not something I have seen before.

The shoulder seam, if you can see it, has been sewn by machine, as has the sleeve. There seems to be a lack of consensus on Savile Row about the best way of doing these operations.

The front of the coat has been stabilized with a piece of black fusible in the pocket area, and the pocket jets have been fused with a white fusible. More on this in a moment.

The fabulous rope has been wadded with a commercially-prepared sleeve roll; a layer of needle-punch felt folded over a layer of canvas.

Now, going back a bit to the presence of fusibles in this coat, as I can already hear the gnashing of teeth. The pocket has been stayed with linen holland in the traditional manner, as well as the piece of fusible so rather than replacing one thing with something more expedient they have rather added another level of construction. The front tape may be fusible but no time has been saved in its hand-sewn application so it is clearly not a time- or cost-saving thing. There were a number of other areas stabilized with fusible tapes in addition to the traditional methods of staying. I think that some of the surprising elements show a bit of forward-thinking which is refreshing for the Row (even if I do not understand them), and may be a sort of double-bagging to ensure the longevity of the garment and in no way represent a cheapening or lowering of standards despite our general aversion to all things fusible and modern.

The owner may not be going into the trenches with this coat on, but I am reasonably certain that he could.

EDIT- little message for Libermann, since I can't remember how to type in Russian. Have a good look at that video you posted....