I recently posted a tutorial on a forum about touching up a suit, with the admonition that you should never steam a suit or hang it in a steamy washroom. I received a number of replies that people saw absolutely no harm in doing so and that they had been doing so for a long time. I found it odd that, despite several tailors on that forum all insisting that one must not steam a suit, people insisted that they knew better. Having taken a deep breath, I realize that not knowing the importance pressing plays is tailoring a suit it would be difficult to understand the effects of steam.

I will say that pressing, which includes the shaping before, during, and after tailoring, plays one of the most important roles in shaping a suit, more so than many of the sewing operations. To illustrate the point, let's look at the shaping of a sleeve.

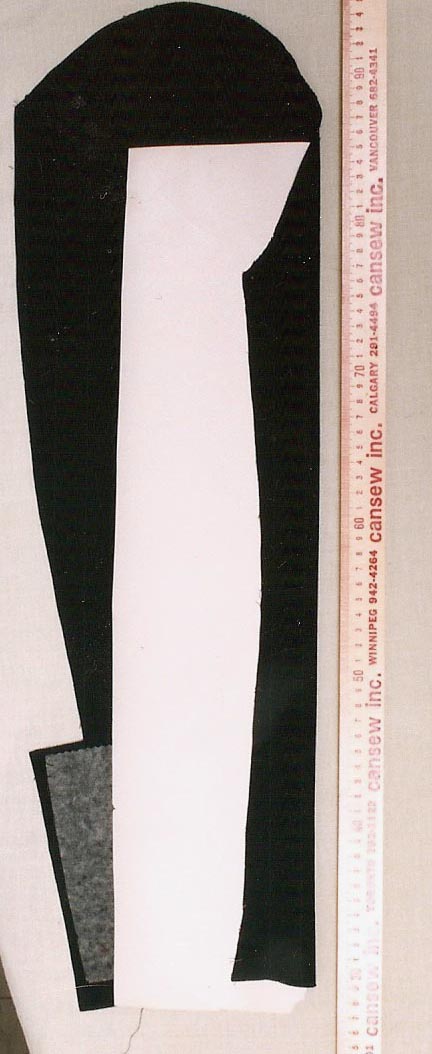

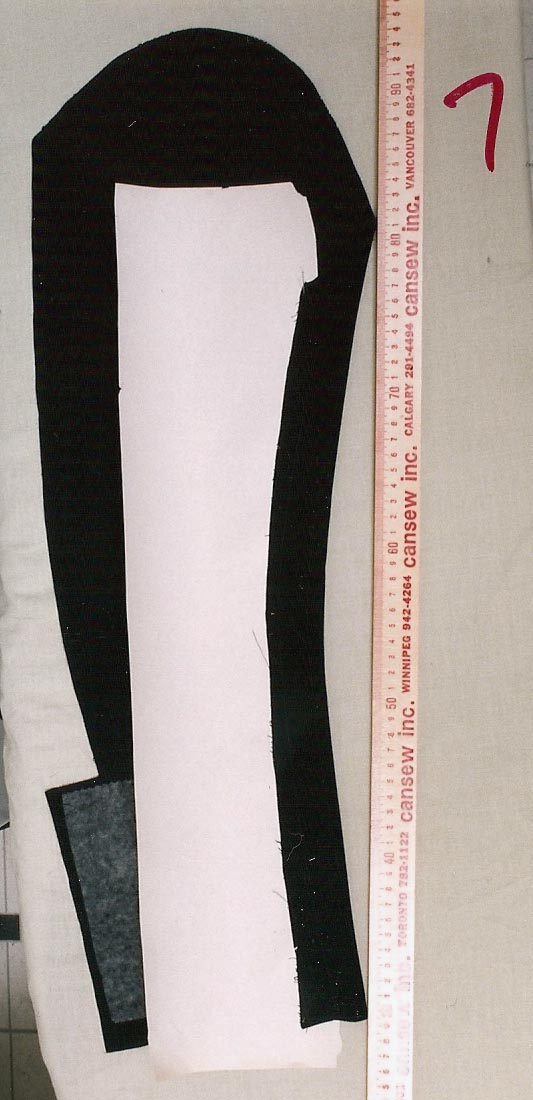

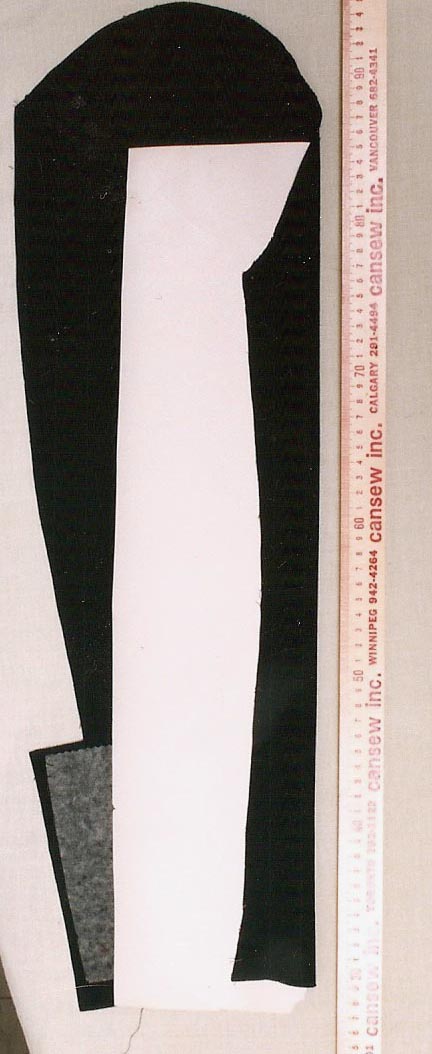

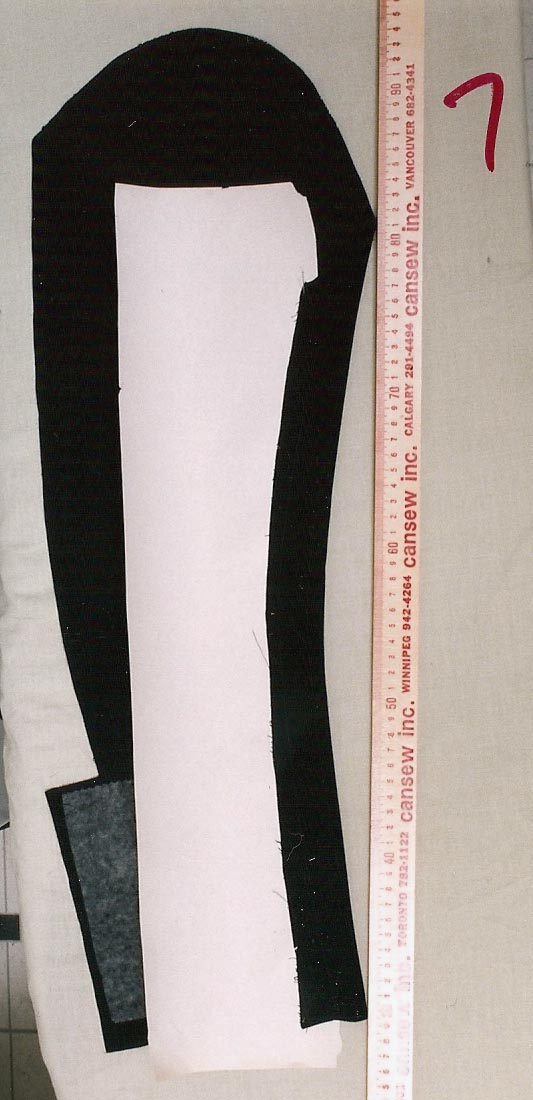

Look back at the photo of my suit and have a look at the way the sleeve curves to follow my arm. To do this we need several seams and some careful pressing. The elbow seam follows the outside of the sleeve, but the seam at the front of the sleeve is tucked 3/4" to 1" inside the fold of the sleeve in order to conceal it. In the photo below, observe carefully how the lines of the check on the undersleeve are straight but the top sleeve are very curved. This is not at all natural.

Normally we need a seam at the exact place that shaping will occur, that is to say, right along that front fold, not 1" back. If I fold the topsleeve back in its natural state, observe below that not only is the front of the sleeve straight, but the curved edge goes in the opposite direction from that which we want. Here comes one of the bits of tailoring magic.

I will use a great deal of steam and pressure, holding the iron in one hand, pressing down in a very specific method, and carefully stretching the top sleeve the length of the curve. There is technique to this that must be learned properly or the sleeve will never hang properly. Using steam and heat, I have re-shaped the top sleeve and re-set the shape, much like using curlers or a curling iron on hair. It is no longer a flat, two-dimensional piece of cloth, but has a shape. Folded into position, the seam now takes its proper shape and the sleeve will curve with my arm.

Just the way I used steam to shape the sleeve, if I use steam on the sleeve without holding its stretched, curved position, I will undo this shaping. The sleeve will relax and hang straight instead of curving, and the tension created will cause a small break just below the elbow. It is a subtle thing to some, but to tailors it is glaringly obvious. It is one of the first signs that a suit has been mishandled. You probably never noticed before, but maybe now you will. And this is only one piece; not a piece of a suit (and there are many) is left flat, without any of this sort of manipulation, and steaming a suit can undo it all. You may not see it at first but you can learn to see it, and put your steamers away.

BY request, here is a tutorial on touching up a suit which I originally posted on Style Forum.

A large part of the beauty of a tailored garment is due to the shaping and molding imparted by a careful and elaborate pressing. In a manufactured garment. there are over 20 different underpressing operations and around 15 steps in the final pressing, most of which have specially-designed forms and machines. Pressing is an art which takes a long time to learn and it is not within the scope of this post to teach proper pressing; I will, however, attempt to show you how to touch up a garment at home without wrecking it, since bad pressing or steaming can ruin a well-made garment.

Wool is a hair, like human hair, which can be shaped using heat and steam. Think of a lady putting her hair in curlers and sitting under a hair dryer, or using a curling iron. We use the same principles when building shape into a suit.

First of all, NEVER use a steamer on a suit, and never hang your suit in a steamy bathroom. This bears repeating. NEVER use a steamer on a suit, and never hang your suit in a steamy bathroom.

A steamer will undo all the shaping that was created when the suit was made, and steaming a suit can also make problems appear such as puckering and blown seams, breaking sleeves etc. I know a lot of people enjoy the ease of a steamer or hanging a suit in the bathroom to get rid of wrinkles, but it is really a very bad idea. There is a video on the internet showing someone pressing a suit with far too much steam and without a good understanding of a suit; during the video the person blows one of the seams, which starts to pucker terribly and she is unable to fix it. It is just this sort of mistake I hope to prevent you making. If you steamed a lady’s hairdo which hat been set using curlers or curling iron, the hairdo would fall limp and lose all its shape- you wouldn’t do this and you won’t do it to a suit for the same reason. Also, when pressing, let the area you have pressed cool and dry thoroughly before moving the garment since it is still malleable and you can cause more problems; do not press until the fabric is dry as the fibers will become brittle- factories and pro pressing equipment use vaccuum to draw the excess steam and heat out so the process is faster.

Have a look at this video (with apologies to the woman who posted it)

[url]http://www.expertvillage.com/video-s..._iron-suit.htm[/url]

The first thing to address is your pressing equipment; if you only have an ironing board to work with the weight of the jacket falling off it will make it very difficult to control, you also need something to work smaller areas like the sleeves. For this reason I suggest getting, or better yet, making a good sleeve board. Lower your ironing board to about hip level and place your sleeve board on top of it.

You will need a press cloth, a bowl of water, and a small sponge or rolled-up wash cloth. To make a press cloth, get a fairly heavy cotton drill from your local sewing supply store and was it a few times to get any sizing out; a press cloth is important because it helps prevent the shine that is extremely difficult to remove.

Have a look at my finished garment- it is not flat, but made up of many shapes and curves- the convex curve of the chest, the concave curve of the waist, yet another convex curve at the seat, the complex shape of the shoulder, the gracefully curving sleeve, the rolling lapel, the curve of the collar as it hugs the neck, and so on. Your pressing surface is flat; pressing a shapely garment on a flat surface will generally ruin the shape of the garment, unless you know how to work with the shape and the surface.

In the sewing process we use 3 techniques to build shape-

Darts and seams, in which the shape is built by sewing.

Easing- drawing fullness or excess cloth onto a tape or another seam.

Stretching and shrinking using heat and steam.

If there are stripes or checks in your suit, it helps to observe them as they will show you where you are distorting your suit as you press it. When I say to "keep it short" it means you should be trying to shrink the cloth a little and be careful not to pull or stretch at all- this is crucial to the shape of your garment.

The worst areas will be behind your knees, the crotch area, the elbow of your sleeve, and the back of your jacket. Remember you are PRESSING your garment, not ironing it; do not rub the iron all over the place. Use steam sparingly, since your iron will send steam all over the place and not necessarily where you need it. If you have a small crease or impression in an otherwise good area, moisten the press cloth just the size of the crease and press- this way you will elminiate the crease without possibly disturbing the rest of the garment or causing new impressions.

The pant is pretty straightforward- using a press cloth and a fair amount of steam, place the sleeve board inside the leg and press out any creases in the crotch area. Be careful around the fly, using less steam, as it is difficult to press it well without making marks or puckers.

Now place the pant flat on a regular ironing board, lifting one leg out of the way. Press the creases first from the inside, then from the outside, being careful around the seam area- the thickness can cause you to blow the seam on the other side of the pant. Many tailors will shape the pant leg by gently shrinking the crease behind the thigh.

Now on to the jacket.

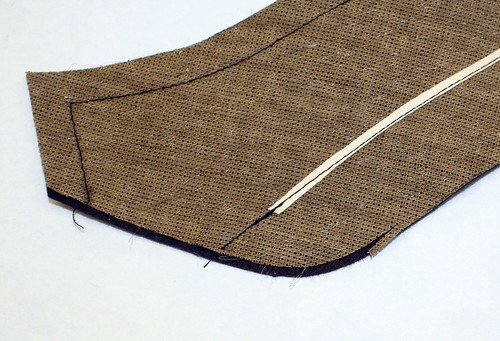

Place the back on the sleeve board, centering the side seam. If the jacket has side vents, place a piece of heavy paper under the top layer of the vent to avoid making an impression on the under vent. Press the seam carefully. At the top four inches or so of the side seam, as well as along the armhole and shoulder seam we have worked some fullness- the back is longer than the side body and the back shoulder is quite a bit longer than the front shoulder; if you steam this or press without adequate pressure you will blow the seams and they will pucker. Be careful not to touch the sleeve with your iron. Keep the seam short- do not stretch it. Lift the vent away and press the undervent.

Work across the back, keeping the area between the shoulder blades short. If you have a center vent, use the same technique as for the side vent.

Centering the side body on the board with seams toward the edges, press the side body keeping the waist short so as not to ruin any of the suppression. The top four inches or so of the front is longer than the side body- there is some fullness in this seam which will also pucker if you are not careful.

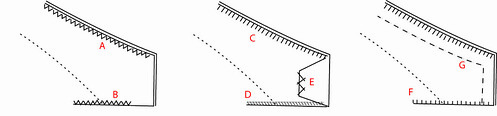

The front is one of the easiest areas to wreck and one of the most obvious when you know what you are looking at. Look back at the photos of the finished garment and observe the shape of the chest. This is built by the front dart, but also some maniuplation of the armhole- there are several layers of canvas unerneath to help build up this shape. When working on the front, ALWAYS keep the dart along the edge of your board, and NEVER place it flat on the board like this;

If you were to press the chest this way, you would flatten the chest, and you will likely see some blousiness under the arm as the extra fabric collapses.

Lay the front of the jacket, lining the dart up with the edge of the board and press the front area as shown. Make sure the stripe is straight. If you must press the flap, place a piece of paper under it before pressing, then lift it and remove any impressions, the same way you pressed the vent.

Press the rest of the front, again lining up the dart with the edge of the board, being careful to keeep the lines straight as you go around the armhole. Be careful around the sleeve cap not to use too much steam since you don't want to disturb the sleeve.

Press the lapel and collar as shown, lining up the roll line with the edge of the board, being careful not to remove the crease since you will have a hard time recreasing the collar and lapel. Try not to touch the collar too much as you will likely stretch it and it will not hug your neck anymore.

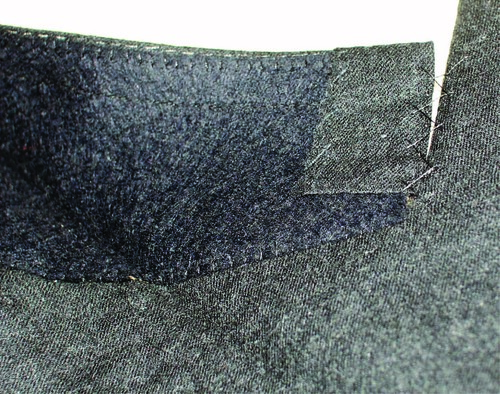

To press creases out of the elbow area, insert the sleeve board into the sleeve with the under sleeve showing, lining up the back seam (outseam) of the sleeve with the edge of the board; the inseam of the sleeve (the seam along the front) should be about ¾” in from the edge. Achieving a well-curved sleeve is a minor miracle of stretching, shrinking and pressing, so be careful here.

Insert the board into the sleeve, keeping the curve as shown, and press out any creases.

Flip the sleeve, keeping the outseam along the edge of the board, and press the top sleeve.

Now place the jacket over the board, and press the top of the sleeve, but stay away from the amhole seam as you could wreck it there.

If you have blown any of the seams (if they look a little puffy instead of flat), reduce the heat of the iron, turn the steam off, and give them a gentle press.

After cleaning your suit will need a good press- if you suspect your dry cleaner uses the inflatable steam bodies, or does not do a good job pressing, innist that they not do it and find a good presser or tailor to do it for you. It will cost more but is a good investment for the appearance of your suit. If they will allow it, watch them as they press- you will develop an appreciation for the real complexity of it and the care that goes into a good pressing.