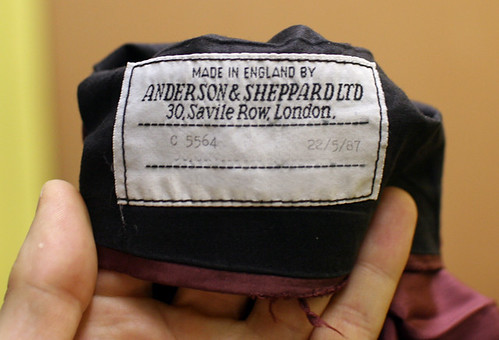

The name of Steed may be new to you. Currently run by Edwin De Boise, it was originally a partnership between two men. Edwin, who comes from a family of tailors and who had worked under the legendary Edward Sexton, met Thomas Mahon when he worked at Savile Row's Anderson and Sheppard as a cutter. The two of them struck off on their own to start Steed, and when Mahon left to pursue other things, including, eventually, his own firm and blog, English Cut, Edwin stayed on and is now training his son, Matthew, in the craft. The dinner suit which comes to me from London dates from the year 2000, a time when the two cutters were still together.

I'm not sure what I was expecting to find on opening the parcel, but given that I have been underwhelmed at best by what I have been looking at lately, my expectations were not high. Granted, the Steed garments I have seen in photos on the internet appear to fit well, however, photos of any sort are not always the best indicator of either fit or quality. In any case, we are starting to have an interesting sampling of garments- we have looked at a moderately-priced dinner suit from Samuelsohn, a more expensive dinner jacket from Brioni, and now a Dinner suit from a Savile Row craftsman. We also have garments from the 3 biggest names on Savile Row and now one of the smaller guys.

This suit is a one-button, peak lapel with grosgrain facing and side vents, and a double-pleated trouser with side adjusters. There is no separate side body, no front dart, and only a small underarm dart. Despite this, there is a decent amount of shape. The lining colour is actually the purple shown in the scan of the label- my lights turn the lining a pinkish shade when photographing. The trouser and the coat were let out by an alteration tailor who did a crummy job, so a few details will have to be ignored- I think it's safe to assume that, instead of sending the suit back to Cumbria for alterations, the owner had someone local do it.

One of the first thing I noticed (and have noticed on Steed's suits before) was the buttonholes. Not only are they individually well-executed, but getting them all lined up evenly is sometimes a challenge. Readers may recall the Huntsman suit which was nowhere near as well done. Upon closer inspection I noticed that the buttonholes had been sealed with some sort of gummy substance; it is common to seal them after cutting and before working them with beeswax- this helps prevent fraying and gives a more solid edge to work with, though it doesn't always work. Instead of using wax, it appears some sort of rubber cement has been used; whatever the case, if this is the result, I am all for it.

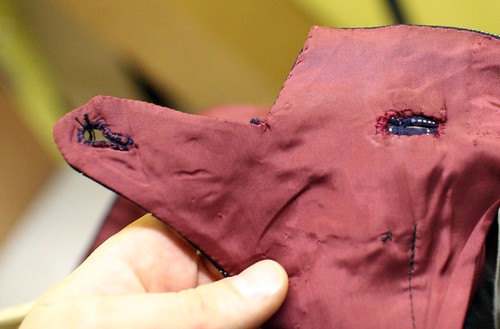

Another thing that is immediately apparent is the neatness of the trousers. Remember these, from legendary Anderson & Sheppard?

How much neater are Steed's trousers....

There is no knee lining in the trouser, like the A&S suit; the finishing of the inside is much neater. The pocketing could stop bullets, but if you lived in a high-crime area that might be a good thing. On the whole, I am impressed wit the trousers, the alteration job notwithstanding.

Oddly, the jacket seems to have taken more wear than the trousers; the cloth is showing some signs of pilling, which is one of the hazards of milled-finish cloths (the ones with a slightly fuzzy texture). While softer to wear and more resistant to shine from pressing than clear-finished cloth. I don't think it would be noticeable to any but the most observant or anal (are you reading this, Louche?) but it's something to consider when selecting cloth if you intend to get many years of wear out of your suit.

The interior pockets are constructed differently than the ones we are used to seeing from Row tailors, and they are neater. They are not anchored on a cloth extension, but this is to be expected when using grosgrain, which is too bulky for it. It's also the first time I have seen a tab closure on an inside pocket from Row tailors.

I won't bore you with all the details of it, but the facing construction is clever. Flannel is required on dinner suits to prevent the interior construction leaving impressions on the delicate silk and there are several ways to attach it. In this case, the flannel was assembled with the lining and machined onto the front as though it were a facing, which can make for a smoother edge, the flannel was basted onto the canvas with a few rows of stitches so it wouldn't shift, and then the silk was felled by hand over top of the flannel.

The finishing of the inside of the jacket is generally as neat as the trouser; comparable, I would say, to the Poole coat, and far better than the A&S.

The canvas, of course, is constructed by hand, using a fine hair canvas. The chest has a full piece of haircloth, but a softer one than we often find in more constructed garments. Since both cutters were A&S alumni, I expected a chest construction like the A&S, in which the haircloth was cut away from the armhole, allowing the draped fold to form, but the canvas goes right into the armhole. With Edwin's varied experience, one can imagine he is able to give his customers what they want whether it is very soft and drapy or slightly more structured. The proportions of the garment do not suggest any great amount of drape either.

The sleeve has two layers of the same flannel as is used on the chest and to face the grosgrain (readers will remember than Huntsman uses four layers) and the shoulder has one small layer of wadding finished with lining, in the same manner as A&S, giving a very soft shoulder.

On the hand-sewing debate, the shoulder seam and sleeve setting were done by machine. Not that I think this is a minus, in fact, recent experiments have debunked some of the claims about hand-sewn seams. One thing I think we are mostly in agreement about, though, is that the armhole should be hand-finished, if not hand-sewn. This means the wadding, canvas and lining are all affixed by hand. In this case, however, the sleeve lining was affixed to the body lining by machine and was loose in the armhole; not only is this very curious, it is also not typical- the photos of recent Steed garments clearly show hand-finished armholes.

Though we might reasonably expect the general quality level to be lower from smaller firms than from the big Savile Row names, especially given the lower prices, this, clearly, is not the case. Maybe they feel they have to work that much harder in order to gain respect and recognition.

Whatever the reason is, it's good.