These days I'm working on a big project, converting a men's suit factory from an entirely fused construction to a half-canvas construction. In fact, to be more technically correct, it should really be called a 2/3 canvas since the coat front we will be using is pretty much identical to a full canvas front but the lower 1/3 of the canvas is omitted. To do this conversion, and generally to bring the factory up to date, we have planned our capital expenditure budget over three years- the very first round of spending being around a million and a half US dollars.

New basters, new sleeve setting machines, new felling machines, new plotters, new pressing equipment, new software, new cloth, new trim, new fits, new patterns... nothing is being left untouched.

While many of the machines have already started arriving so we have begun training people on the new methods, one special set of machines is being made for us in Germany so won't be in for at least another month. The Strobel KA-ED single thread rollpadding machine is a pretty neat piece of equipment. To hand padstitch a lapel the traditional way takes up to an hour per pair, one left and one right. You roll the canvas portion of the lapel over the cloth, invisibly stitching the canvas into place while maintaining the rolled shape, so that the shape will be permanent. A fused lapel has none of this rolling so the shape is pretty limp and lifeless, and has a tendency to curl away from the chest. These machines, however, can execute a similar action, rolling the canvas over the cloth while stitching invisibly, but do so in about a minute. The machines come in pairs, one for the left side and one for the right, and the operator places the coat on the machine, lining up a guide with the roll line of the coat. The machine has sensors which see the start and finish of the cloth, so it knows where to start stitching, and knows where to stop. Beginning at the roll line, it sews a line of invisible stitching, stopping at the top of the lapel, then like a typewriter carriage, stops, returns to the beginning, and rolls the lapel, advancing a row, ready to start the next row of stitching. The operator can place one coat, then forget it, setting up the next machine while the first is sewing. A good operator can run two pairs of machines, or four sewing heads, rotating between each so that one is being set up while three are sewing. In an eight hour day one person could easily do eight to nine hundred coats this way, compared to the six to ten coats you could do if doing them by hand. It comes at a price, though. Each pair of machines costs almost one hundred thousand US dollars.

Padding by hand

Padstitching from Jeffery D on Vimeo.

Grabbed this video from the internet, I think it comes from a Turkish factory, showing an older model of the Strobel machine in action.

EDIT

Josch of Pattern Design Analyst asked how we will do the shoulder construction. We are changing pretty much every single step of the coat construction, going from a two-shell construction back to a modified open coat construction.

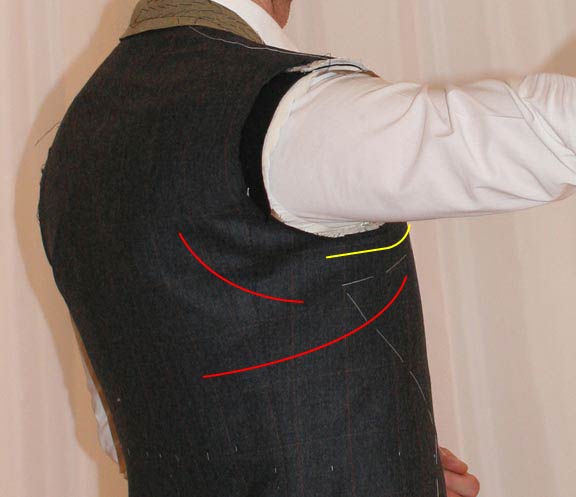

Currently the sleeve head is attached to the sleeve with a shirring machine, then the sleeve is set to the coat, going through the chest piece. Obviously the seam can not be opened so you get a rope shoulder effect which they then attempt to press down. This will all change.

We will have two basic shoulder constructions- one for most of our production and then a softer variant. The basic one be done as follows-

When shaping the fronts we will also measure and trim the canvas in the armhole, leaving the armhole free from the canvas.

Attach shoulder pad to the chest piece with a jump baster.

Later, set sleeve through the coat only, then press the seam open.

Baste the armhole into the chest and shoulder pad from the outside.

Baste the lining around the armhole, then set sleeve head and trim armhole.

Close armhole lining.

For the softer shoulder we will do something similar to a spalla camicia shirt sleeve- set the sleeve as above, sew in a 3/4" bias strip of silesia at the top of the sleeve, and press the sleeve and armhole seam allowances toward the coat.

Baste the armhole into the chest from the outside- the silesia will be used to secure the top of the armhole into the canvas. The rest is the same, but using only a very fine sleeve head (or none at all, depending)

So far we have had decent results. We got in new Durkopp sleeve setting machines yesterday and we like them a lot. We also got a series of finish pressing machines which we will install next week.