I didn't get a chance to photograph the blazer before shipping it, sorry. To make it up to some of you (well, at least to Kim who has been begging for this for a while) some thoughts on setting sleeves. Not a full tutorial, but just a few pointers, this time a woman's overcoat. (Cheating, she says- those sleeves are easy!) This will appeal mostly to homesewers, so if that's not you, check back soon when I will be opening up a Caraceni that is somewhere in the postal system (I hope it's not lost!)

The first thing I will mention is the importance of stabilizing your armhole- if you distort it by even 1/8" in some areas you can have sleeve trouble and will have to adjust the pattern. The most common way of doing it is to stay the armhole with 1/8" cotton india tape, drawing in slightly in the sharply curved area of the lower part of the armhole. By drawing in, I mean to pull slightly on the tape to shrink that area a bit.

With very full sleeves or difficult cloth I will pre-shir (gather) the sleeve. In the factory we have programmable machines that will shir different amounts around the sleeve cap; at home I will just use a long stitch on the plain machine, run two rows, and draw them, easing the cap into a nice shape. Make sure that the shirring is smooth and that there are no areas that are puckery or lumpy- also, no easing for about 3/4" on either side of the shoulder seam notch.

If you haven't altered the armhole and are working from a commercial pattern, then you are good to go, matching notches- if you have eased the cap you shouldn't have much trouble basting it in; any puckering that shows up should be redistributed. Don't be tempted to fill in a puckery sleeve with a bunch of wadding- it may hide the puckers now, but they will come back. The wadding is just to help the sleeve, not to cover bad sleeve setting. But let's say you HAVE changed the armhole a bit during fittings, or, like this one, it's a new pattern that hasn't been tested yet. Then you may have to adjust a little.

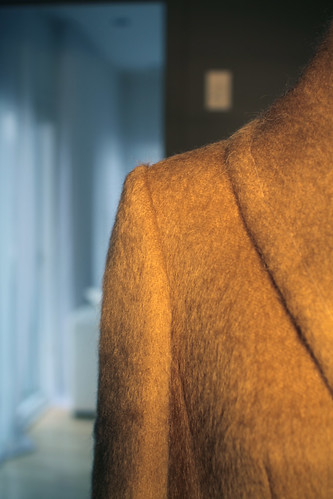

There should generally be more fullness toward the front of the sleeve, near the front of the shoulder bone, than in the back. I have basted my sleeve in, and the back looks good,

But the front is too full- I don't want that much of a rope. Maybe you have puckering because the sleeve is too full or the cloth is difficult.

I take the sleeve out, remove the shirring stitches, and rip the elbow seam. Then I trim the top sleeve a bit (or a lot, in this case) like this

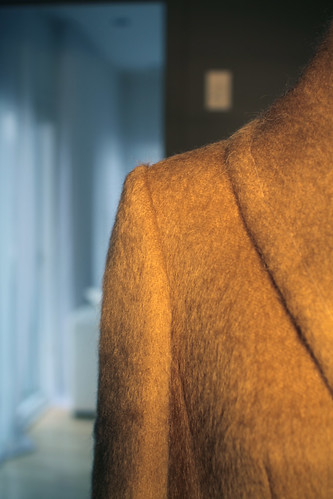

Then I re-sew the elbow seam, redo the shirring, re-baste the sleeve, and hope for the best. Lather, rinse, repeat, if necessary. The result is much better.

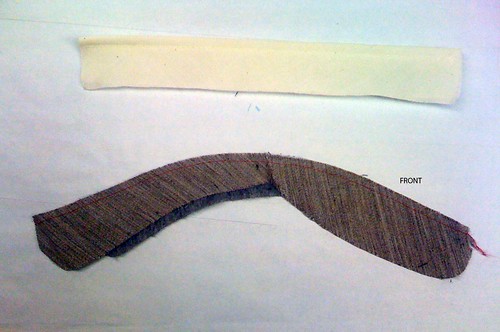

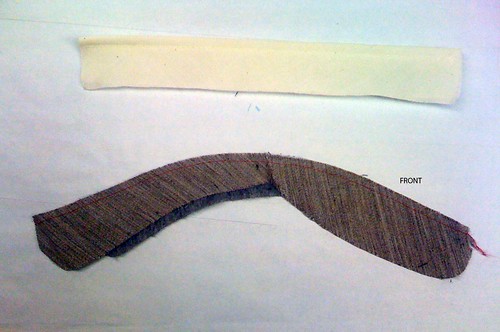

Then I will cut some wadding and canvas for the sleeve head, which will look like this-

The two pieces of canvas go on the front, with the smaller piece underneath- note how the hairline reverses on the pieces- very important. At some point I wrote an article on designing sleeve heads so I will try to dig that up rather than going into too much detail now.

EDIT

Here's the post

ot about shoulders in tailored clothing. One important element in defining the look of the shoulder is the sleeve treatment; first, the seam can be put toward the sleeve for a rope, it can be opened for a continental shoulder (one with a defined crown but no rope) or a natural shoulder, or it can be put toward the coat for a neapolitan shoulder.

Second element is the type of wadding used. The traditional wadding was usually a piece of lambswool with a bias-cut cotton folded over it (see photo, item on top of crappy iphone photo). The disadvantages are that this can be a bit lumpy, it is limiting in the style of shoulder you can achieve (it tends to be ropy) and it tends to break down over time. We hear a lot about traditionally-made coats “settling” over time; I, personally, would rather deliver a garment which will keep its shape over time, rather than one that changes. But that’s me.

The wadding shown in the lower part of the photo is more common in RTW garments now because it affords more control to the designer and will keep its shape. It also helps with the dreaded “hanger appeal”, which bespoke tailors don’t have to worry about.

Two types of felt are commonly used- one is a basic needle-punch felt with a foam backing which is quite lofty and good for rope-style shoulders, the other is a needle-punch felt with a scrim (net) backing which is lighter and softer. I, personally, prefer the scrim felt for all applications over the foam but the foam keeps its shape better.

The canvas used is a special weave designed especially for, and only for, sleeve heads. It is a broken twill weave and is denser and has more roll to it than regular canvas. It is easy to tell the difference when you look at the back of the canvas. The canvas helps support the sleeve not only on a hanger, but on the wearer, and prevents disasters happening if the wearer should inadvisedly steam his suit

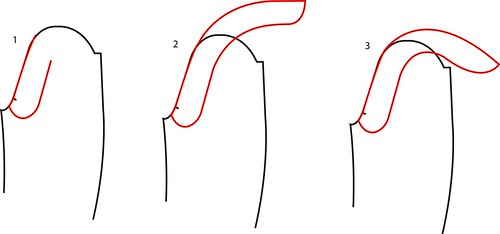

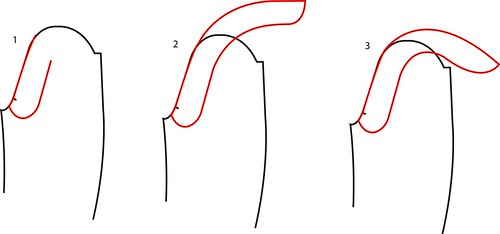

The pattern for the sleeve head will depend on the type of shoulder you want. It starts with the sleeve pattern; start shaping the sleeve head as shown in figure 1. The degree of curve from this point will determine how much bulk you introduce into the sleeve cap- for a rope shoulder or one with a very defined crown, make a straighter shape, as in figure 2. For a natural shoulder (and by this I mean of the J Press/Southwick/Paul Stuart type) make a much more curved shape (figure 3), which will make a flatter profile with less bulk. From this basic shape you can develop your pieces.

For the felt piece, I don’t run it all the way down the front, though some do- it’s up to you. The first piece of canvas that you make will support the sleeve and define the crown (or not)- for a rope or continental shoulder, start the canvas about 2” down from the shoulder point. Be very careful to observe the HAIRLINE indicated on figure 1. I indicate the hairline and not the grainline because the canvas is streaky in the direction of the hair line and is easy to identify visually (the hairline is the crosswise grain). The large piece must be cut on the bias with the hairline RUNNING DOWN or you will get a dimple on the cap. A second, smaller piece is usual, as shown in green on figure 2. The hairline is also bias but the opposite to the large piece- this will ensure a nice forward roll on the front of the sleeve. A third piece can be cut, as shown in orange, on figure 2. Note the direction of the hairline.

A natural shoulder requires less canvas. The scye seam should be opened as much as 4” to either side of the shoulder point, and there should be no canvas in this area. It’s not as clean on a hanger, but is nice on the wearer. Start the canvas 4” down from the shoulder point as shown in figure 3. There should be no canvas in the top of the sleeve, and a third (sometimes fourth) piece is added to the back, as shown in orange.

A certain amount of experimentation will help you develop a sense of how the shape and size of each piece affects the final contour of the sleeve cap.

Now back to watching my mail box for that Caraceni....